How High-Performing Systems Shape Teacher Quality

a forum hosted by ACEL

at NSW Parliament House

The Hon. Rob Stokes MP (current NSW Minister for Education)

Member for Murray Adrian Piccoli (former NSW Minister for Education)

Ann McIntyre (ACEL NSW President)

Aasha Murthy (ACEL CEO)

ACEL is the Australian Council for Educational Leaders

‘Parliament House c.1829’

Flickr, Government Macquarie account

https://www.flickr.com/photos/sydneyhistory/6634269541

This was an evening about handing over the baton, one education minister to the next. Both were humble and gracious. Both presented as remarkably intelligent, demonstrating much depth in their knowledge of education and education systems.

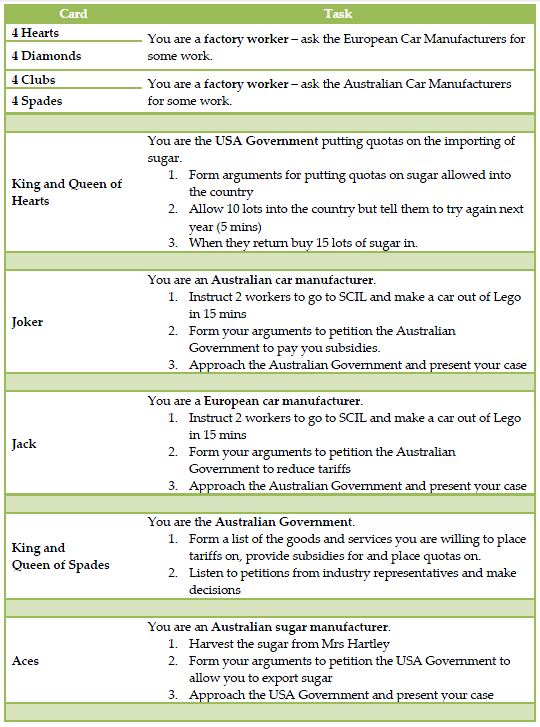

The forum commenced with the President of ACEL NSW, Ann McIntyre, introducing the context of the forum title. The topic stemmed from a study led by Linda Darling-Hammond, conducted over three years in several education systems/jurisdictions in Canada, China, Finland, Norway, USA and Australia. The subsequent book, Empowered Educators: How High-Performing Systems Shape Teacher Quality Around the World, thus provided the forum its title. There is also a version that focuses on the Australian part of the study, Empowered Educators in Australia: How High-Performing Systems Shape Teacher Quality. Both books were co-authored by Ann. Somehow, Ann managed to summarise the findings of the study quite neatly (provided here as a mixture of verbatim and paraphrasing).

The key to education improvement is:

- Teacher quality

- supported by policies and practices established within the system

- with a balanced assessment system

- and a progressive needs based funding model

To enable this to occur the research showed school systems need:

- Good recruitment procedures

- Teacher preparation/training for deep knowledge and pedagogy

- Timely and quality professional experience and mentoring

- Continuous professional learning

- Opportunities for professional feedback, focused on growth/improvement

- A career and leadership development program

To achieve all this, schools need resources and opportunities for collaboration.

Key features of NSW and all the other jurisdictions studied in this research project were:

- High social regard for teaching (disputable in NSW)

- Selectivity into the profession

- Deep financial support for preparation of teachers and professional learning throughout career

- High integrity in professional standards

- Preparation and induction grounded in very well defined curriculum content and how it is taught

- Teaching that is research informed

- A collaborative profession, not operating in isolation

- Professional learning across a continuum

- Well-developed leadership that captured and foster the highly skilled teachers

- Systems focused on equity and excellence, as seen in the Melbourne Declaration

All this doesn’t happen randomly. It must be through systematic, coordinated reform and innovation. It is important to invest in teaching so that it transforms not just some but all students.

Ann then handed over to the former and current NSW ministers of education. Rob Stokes spoke first, prefacing his talk with a lawyer-esq disclosure that what he was about to say were his thoughts about education, not yet fully formed. He then proceeded to provide an intellectual, although brief, consideration of his philosophy of education. He supports an Athenian model over Spartan model, as in developing the whole person rather than educating for the mere purpose of producing people who can contribute to the state. He believes education should be inclusive and be about preparing learners rather than the didactic delivery of information. He concluded by saying he does not have a reductive view of education but an expansive view so, for example, he is not about merely developing ideas to put into existing classroom situations.

Adrian Piccoli spoke briefly, I suspect to keep the emphasis on Rob Stokes as the current minister. In summary, he said the role of the minister is to facilitate education by providing the right environment, dollars and people to make it function. The minister also needs to be constantly aware that education reform could drift and thus be at risk, although what this risk entailed was not made clear.

Ann then facilitated a Q&A session. Both Rob and Adrian were obviously comfortable in each other’s company, sharing the stage with ease. They were respectful of each other and the audience. The questions posed were pertinent but they were very considered in their responses, even as to who would be most appropriate to answer first.

The themes that emerged from this discussion were:

- Children are at the heart of education.

- Valuing teachers

- Systems vs People

Children are at the heart of education. Rob and Adrian are very proud of NSW having needs based funding and even though they can see flaws with the amount of funding dollars out of the Federal Budget this week, they are pleased with the needs based model on which it is based. Relieved, even, that it is now a bipartisan policy. I suspect Adrian Piccoli has had many fights within the coalition about that. On the other hand, there was some regret expressed about the amount of financial contribution to education coming from the federal government.

Valuing teachers more was another recurring point. Rob made the astute observation that at the local level, those actually involved in schools, particularly parents, mainly have great respect for teachers. That said, Adrian suggested parents don’t know enough about what happens in school and that they need to know more about the importance of growth instead of raw scores. He also pointed out that there is a cultural perception hard to remedy, represented partly by the attitude towards teachers having so many holidays, and that someone with a 99 ATAR wastes their intellect on becoming a teacher. He believes this has stemmed from complacency rising from consistent economic success and that accessing university education has become easier. He offered that the best way to help teachers is to buy them more time to think and to collaborate. Easy to say now he’s no longer making such decisions. But he’s right.

Systems vs People is how I would summarise the rest of the discussion. There is a constant struggle in education of quality teaching being hampered by requirements of the system, where the system includes standards, curriculum/syllabi, testing regime (eg NAPLAN and HSC), policies and funding. It limits the freedom of principals to focus on learning over administration and operations, it makes it difficult to be equitable for students with disabilities and in low socioeconomic areas, and testing crowds out more genuine learning.

Generally the discussion was philosophical. Rob returned to the Greek idea and said the purpose of education was to prepare children to make a living and make a life but the social aspect of this being almost impossible to measure. He drew parallels to his previous role as Minister of Planning that a development proposal can measure economic impact but much more difficult to assess social impact, in quantifiable terms. The relational aspect of education is what makes it particularly hard to measure. Adrian suggested that teaching is an art form, not a science. For instance, if you teach two kids exactly the same way, you will still achieve two very different outcomes.

Rob and Adrian were political in their responses when it came to the amount of testing in our schools. Adrian cited the removal of the School Certificate and better understanding of NAPLAN data reducing the misuse of it as success under his watch. He supported the Year 9 NAPLAN becoming a compulsory hurdle for the HSC due to the importance of numeracy and literacy. Rob added that it was important for students to take school seriously earlier and not wait for Year 11 to step-up their efforts. A member of the audience pointed out that NAPLAN is so separate from the day-to-day syllabi that it is perceived as an extra burden, on both students and teachers. I don’t think many politicians and other people outside schools see the level of stress a testing regime places on students. It also places more value on mark obtainment through memorising over learning and thinking skills in a more general sense.

Throughout the discussion I was very impressed with the deeply considered responses Adrian and Rob provided. However, Rob as the current minister and seasoned politician already has his three word slogan for education: equity and excellence. Equity, in that every child matters, and excellence by teachers being exemplars. It told me that he will be putting increasing pressure on teachers. Yes, there are some teachers who ride through with minimal effort but I believe the majority are working extremely hard for their students to achieve and thrive as living human beings.

A tweet from a principal recently stated that senior leadership (but really applies for schools as a whole) is about “keeping young people alive, challenging [their] lifestyle choices and navigating conflicting stories, setting them up for life beyond school but mostly keeping them alive”. She added, “The heart of school is about caring for our young people and bringing out the best in them”. This is what people outside schools need to understand. The system should change to allow more time for teachers to meet the needs of their students and for society to understand what schools are really about, and it isn’t merely an ATAR. Society, the system and schools need to stop treating the HSC and the ATAR as the one and only goal of education. This includes NESA (NSW Education Standards Authority) continually promoting a “Stronger HSC” ad nauseam. It is a marketing slogan, not a description of what education should be about. We need politicians and government representative bodies to be more vocal about the worth of teachers, schools and education in general, and reduce the rhetoric that overly stresses the importance of the HSC. If Rob Stokes truly believes the philosophy of education he presented at this forum, he needs to speak it proudly and loudly, without caveats.